As a disease ecologist, I am interested in how interactions between hosts, microbes, and their environments shape infection outcomes and the evolution of virulence. My work combines experimental evolution, comparative infection assays, and theoretical frameworks to understand why infections vary so widely—from mild to lethal—across individuals and heterogeneous populations.

I have applied my research to host systems such as Drosophila melanogaster, Anopheles gambiae, Aedes aegypti or Caenorhabditis nematodes; and microbes and parasites, such as bacteria, fungi and apicomplexa.

I investigate how host and parasite genetic diversity, parasite transmission routes, and environmental factors drive heterogeneity in virulence, transmission, and pathogen persistence. Ultimately, my research aims to integrate ecological and evolutionary perspectives to better predict infectious disease dynamics and inform both public health and conservation.

Scroll down to learn more about my current areas/topics of interest. Reach out if you’d like to collaborate, or ir you are just up to discuss some science!

Current research areas:

Virulence and transmission

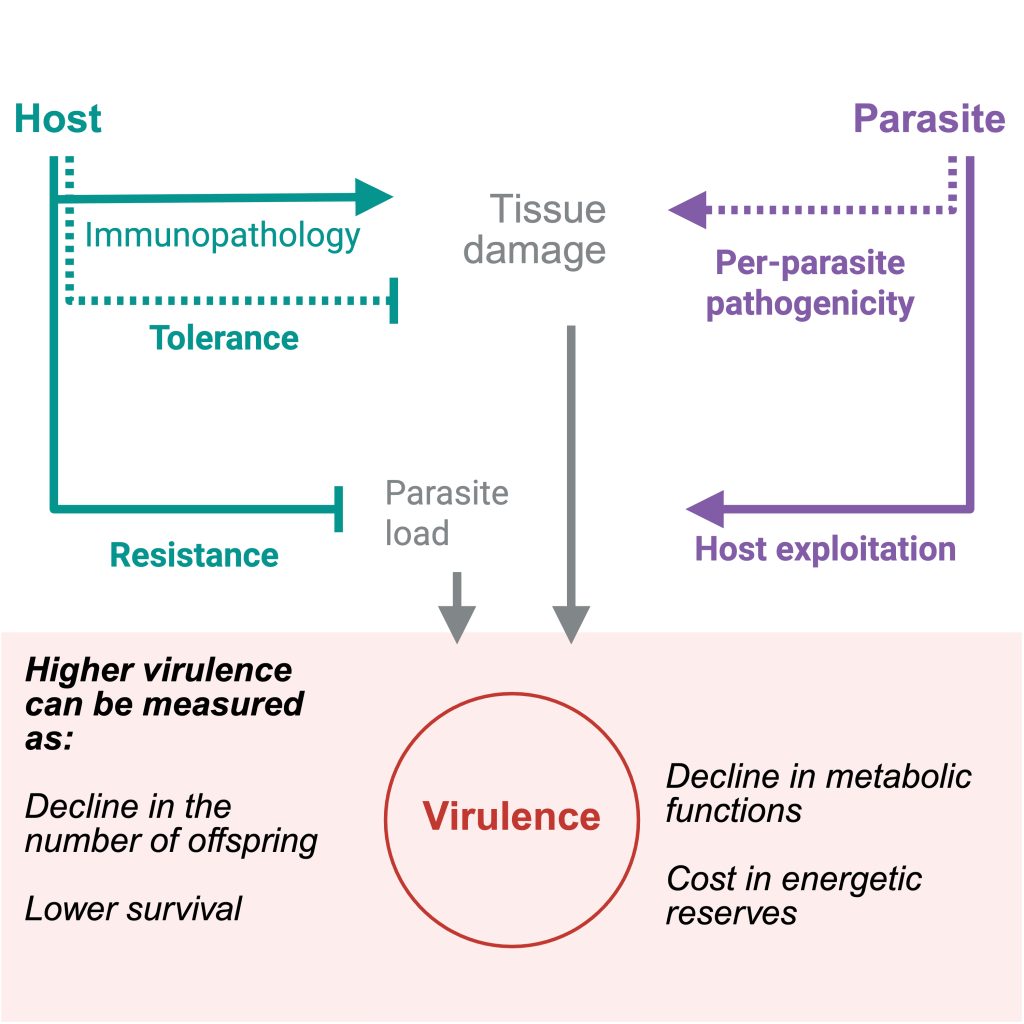

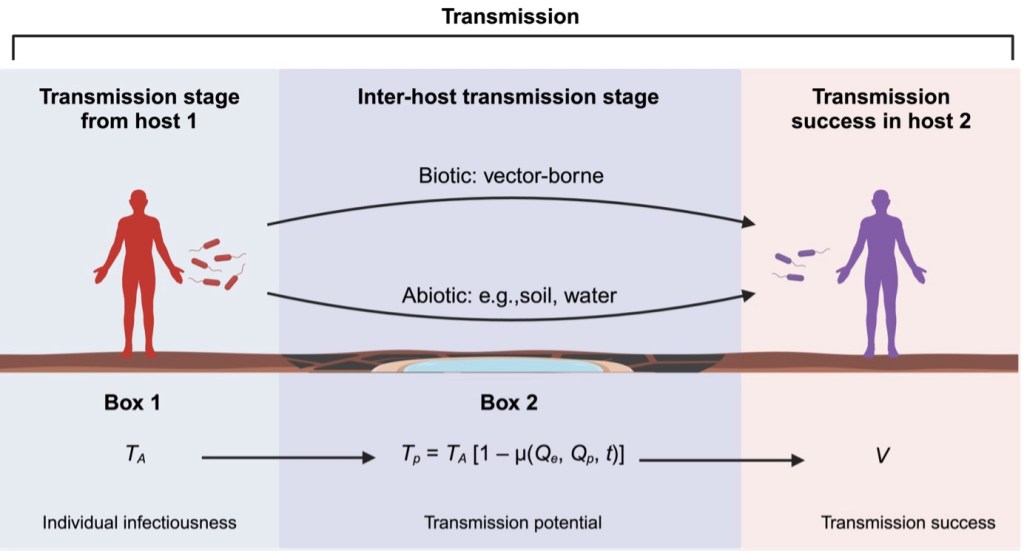

When a parasite infects a host, the outcome — how severe the infection becomes — is what scientists call virulence. Parasites rely on transmission to spread to new hosts, and this is their primary measure of fitness. The two are linked: parasites that cause more harm often face trade-offs in how well they can spread, and vice versa. Yet infection outcomes are far from predictable. They can vary depending on the environment, the evolutionary background of the host and parasite, and the defences or tools each side brings to the fight. In my research, I ask how virulence and transmission change throughout the infection process, what drives this variation, and how understanding these dynamics can help us better prepare for — and respond to — infectious disease threats.

Images credit: Silva & King. 2025. Current Biology. Silva, King & Koella. 2025. PLOS Pathogens.

Symbiosis and microbiome

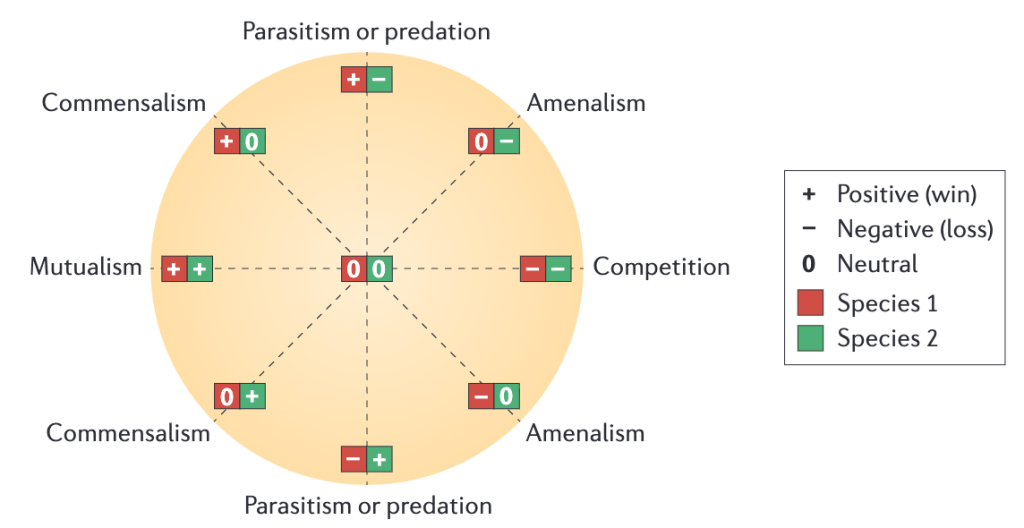

Microbes live in and around every organism, and their presence can be a blessing or a burden. Some microbes help their hosts grow and thrive, while others cause disease. My research explores this spectrum — from cooperation to conflict — asking what turns a microbe into a parasite or a mutualist. I am also interested in whether we can guide evolution to push these relationships toward more beneficial outcomes, with implications for health, agriculture, and ecosystem stability.

Image credit: Faust & Raes. 2012. Nature Reviews Microbiology.

Microbial evolution and parasite LHT

Microbes rarely live alone. Instead, they form crowded and ever-changing communities, influenced by environmental conditions, new arrivals, and interactions within the group. Depending on the context, these microbes can help or harm one another — and in turn, their host. I study how these microbial relationships, from co-infections to long-term partnerships, shape the balance of health and disease in hosts, as well as parasite evolution.

Image credit: Weiland-Bräuer. 2021. Biology.

Aging & senescence

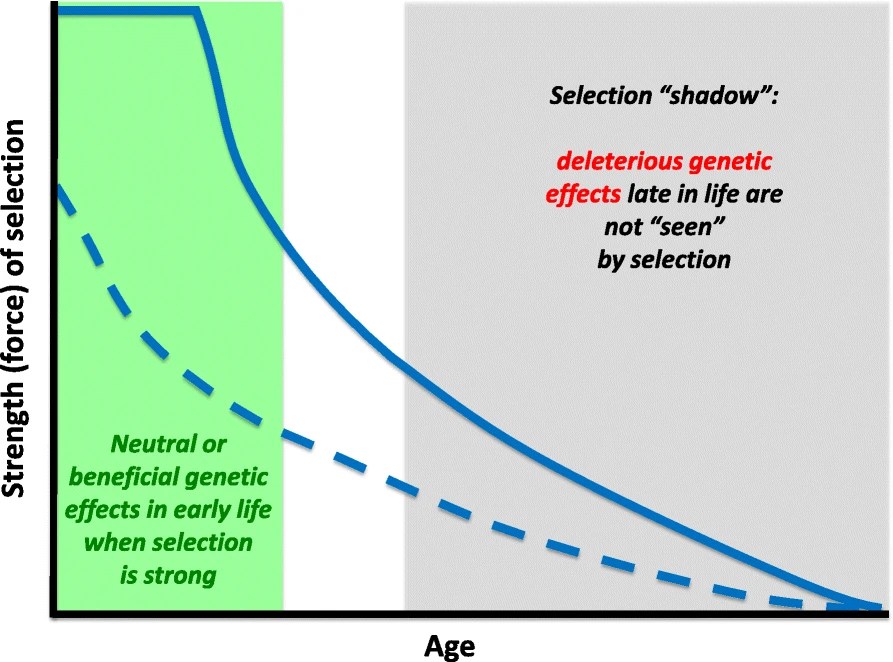

As hosts age, their bodies change—immune strategies change, resources investment shifts, and microbes inside them evolve too. For parasites, older and very young hosts can be easier to infect or may offer different opportunities for growth, meaning disease severity can change with age. Moreover, senescence (and aging) are intrinsically linked to immunity, with many trade-offs observed in all types of natural systems. I study how aging affects response to pathogens, and vice-versa. By combining age-structure and evolution, we are increasing the ecological realism of our research and validating (or not) several ecological and evolutionary expectations, which are essential for epidemiological guidelines.

Image credit: Flatt & Partridge 2018, BMC Biology.

Topics I am interested in collaborating/integrating:

Biorhythms & circadian clock

Our bodies follow daily rhythms that affect everything from sleep to immunity. Parasites experience these cycles too, and some may even “tell the time” by matching their growth or transmission to when hosts are most vulnerable. Understanding how these rhythms influence infections can help explain why the same parasite sometimes causes mild disease and other times severe illness, and shows why timing is such an important—yet often overlooked—part of disease evolution.

Image credit: Rock et al. 2022, Frontiers in Physiology.

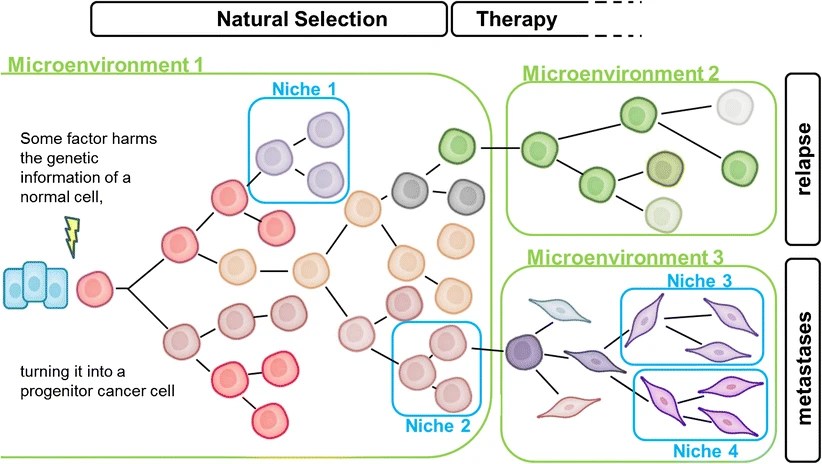

Evolution and ecology of cancer

Cancers and parasites might seem very different, but they face many of the same evolutionary pressures as they grow and spread. Some cancers can even be transmitted between animals, as seen in Tasmanian devils and dogs. Yet tumors are unusual because they arise from the host’s own cells, creating a conflict of identity. By comparing cancer and parasite evolution, we can learn more about both — and gain new perspectives on how diseases develop and persist.

Image credit: Schulte et al. 2018, Cell and Tissue Research.

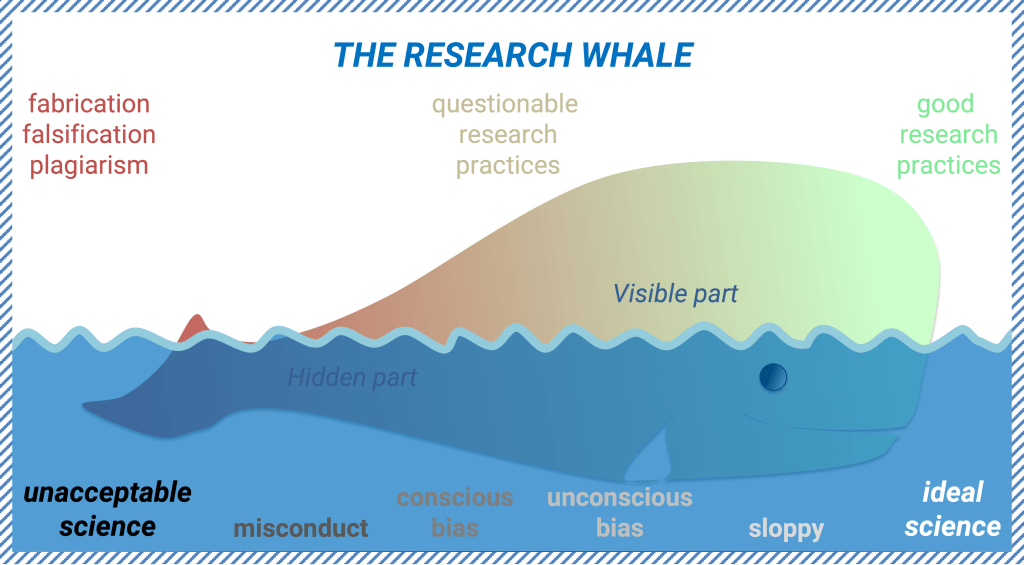

Science transparency, reform & DEI

Science is not yet open or accessible to everyone, and this inequality affects every stage of a scientific career. Real progress depends on diversity — bringing together different backgrounds, disciplines, and voices. Too often, research stays in the lab and misses the bigger picture. For example, vector biologists may study parasites in detail without considering how people protect themselves from infection or how the vector behaves in the wild. To me, it’s vital that scientists learn from the communities who live with these challenges every day. I care deeply about supporting under-represented early career researchers and promoting international and inclusive science. Above all, science should be transparent, approachable, and available to all.

Image credit: Malgorzata Lagisz (SORTEE).

Science communication

Science is too often separated from the public — and even from other areas of science. This distance creates space for mistrust, misinformation, and political misuse of research. I believe it is our responsibility as scientists to share our work clearly and honestly. For me, science communication is about making research understandable, breaking down barriers between disciplines, and building stronger connections between science, education, industry, and society. I am keen on initiatives that promote scientific work for the general public, as science should be open to everyone.

Image credit: Scheufele. 2014. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

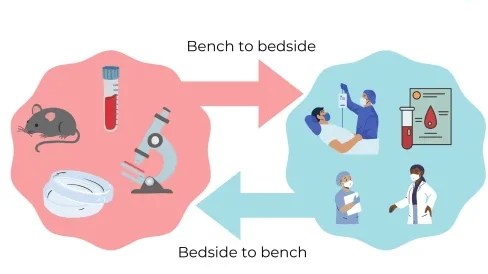

Translational research and personalized medicine /questions

My work is rooted in basic biology, but it also has a high translational value with relevance to medicine. By studying how host and microbe factors shape different infection outcomes, I aim to help predict which scenarios might lead to more severe disease. The model system I currently use (Caenohabditis) develops quickly and comes with a vast library of genetic variants, making it especially useful for testing ideas, screening drugs, and addressing pressing medical questions with speed and precision. Bridging of fundamental and applied research is of the utmost importance for both sides.

Image credit: Labtoo’s team; Drolet & Lorenzi. 2011. Translational research.

If you are interested in discussing or collaborating any of the topics above (or any others), don’t hesitate to drop me an email.